South Baymouth

Little School House Museum – Informs about the community’s early fishing days through displays and artifacts and features the Island’s only remaining one-room school that has been preserved intact.

Ferry Dock – Besides being the loading and unloading point for the Chi-Cheemaun (which makes four return trips a day during the tourist season and two round trips daily during spring and fall), the ferry dock is a nice place to relax by the port.

John Budd Memorial Park – A pleasant park with a nearby swimming beach appropriate for children.

Tehkummah

Blue Jay Creek Fish Culture Station – Operated by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, the station rears young lake trout for release in the waters of Manitoulin and the North Shore.

Fairview United Church – Built as a Methodist Church in 1897, this wood-frame church is surrounded by the gravestones of early members of the community.

Michael’s Bay Municipal Park – Located off the Government Road southwest of Tehkummah village, the park is ideal for picnics, swimming and fishing. The Manitou River and Blue Jay Creek both flow into Michael’s Bay.

Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory

Wikwemikong Health Centre – Uniquely combining the science of Western medicine with traditional healing methods, the health centre is also worth a visit if only for its splendid design. The nearby Hub centre provides children’s services: nursery school, day care, toy library and resource centre.

The Historic Ruins – Large dormitory for Jesuit clergy that burned in the early 1950s located beside Holy Cross Mission Church. A perimeter of solid stone walls, two feet thick and three stories high (minus the roof), are all that remain of the building. Often a venue for Debajemjig storytellers summer offerings.

Bebamikawe Memorial Trail – Manitoulin’s newest trail and outdoor fitness park is located at Wikwemikong. Trailhead is at the end of Beach Road in Wikwemikong. The trail is 14 km of easy to intermediate trails, spectacular lookouts and educational signage. The Outdoor Fitness Park section of the trail is a double track, granular surfaced trail with five fitness stations equipped with outdoor fitness equipment so that trail users can take advantage of resistance training in a scenic natural environment. For information about the trail, contact (705) 859-3477.

Manitowaning

Assiginack Museum – Originally built as a lock-up in the 1850s, the museum contains a range of artifacts from the lives of early settlers in the area and is home to an impressive and expanding collection of antique glassware, porcelain and pottery. The museum grounds feature a schoolhouse, blacksmith shop and barn.

St. Paul’s Anglican Church – The oldest Anglican parish church in Northern Ontario was consecrated in 1849 and still stands serenely on the edge of the downtown, overlooking the expansive waters of Manitowaning Bay.

S.S. Norisle Heritage Park – Located at the Manitowaning waterfront. Home to a nineteenth century grist mill and the Burns Wharf Theatre building. Park includes docks, boat launch, change rooms and a great sand beach. Resting in permanent dockage is the S.S. Norisle, the last passenger steamship to be built in Canada after WWII. Go to www.norisle.com.

Lighthouse – Located behind St. Paul’s Church and overlooking Manitowaning Bay, this operational lighthouse was built in 1885.

De-ba-jeh-mu-jig Creation Centre – Home of De-ba-jeh-mu-jig storytellers and the Kathleen Reynolds Mastin Gallery, in downtown Manitowaning. The theatre has taken over the old Mastin’s Store and amplified it to the tune of 14,000 square feet of space dedicated to theatre (and often other visual arts). Besides a massive black box rehearsal studio with a sprung floor, the two-level complex includes a carpentry shop, a costume shop, space for an actors’ green room and a great deal more. It’s well worth a visit. There are continuous activities there and usually an art installation in the Kathleen Reynolds Mastin Gallery. The old stone-fronted Mastin’s store provides the entrance. You can call (705)859-2204 or consult www.debaj.ca for more information, or just come in.

Sheguiandah

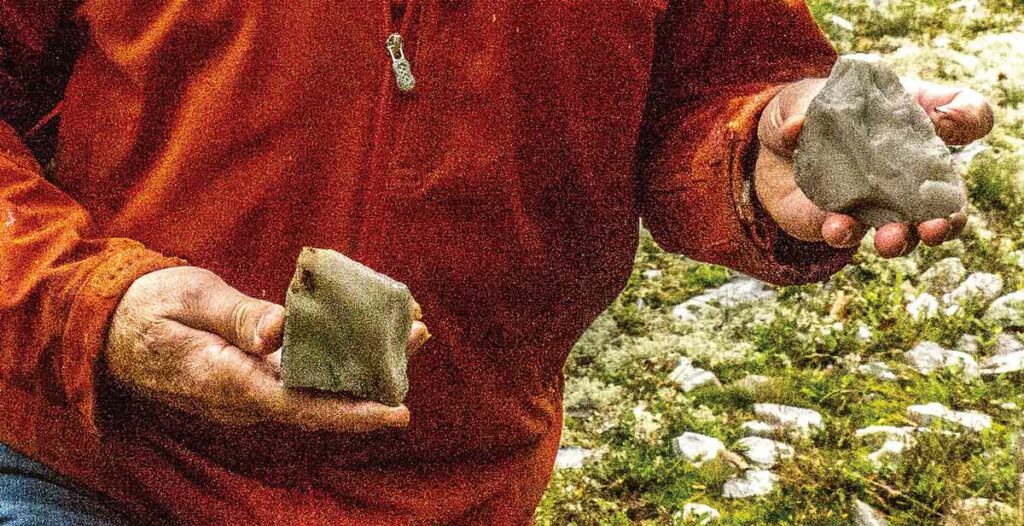

The Centennial Museum of Sheguiandah – The museum projects the life and times of the pioneers who settled here after the Manitoulin Treaty of 1862. Also displayed are artifacts from the prehistoric quarry, as well as the wreckage of a mail plane which was associated with President Roosevelt’s 1943 wartime visit to the area. Each summer the museum curator presents a busy agenda of art exhibitions, workshops and lectures. New installation is an interactive interpretive centre featuring the 9,500 year history of human activities in the community. A replica mill complete with a water wheel, is a feature on Bass Creek.

Hiking And Walks – An available tour map tells the story of nineteenth century Sheguiandah. Also, there are maps to guide you through village landmarks.

Fish Viewing Platform – Spring and fall, depending on the fish species, there is a platform especially available at Bass Creek from where to watch fish fighting their way up river to spawn. This is the joint effort of the Little Current Fish and Game Club and Manitoulin Streams.

Providence Bay

Manitoulin District Cenotaph And Memorial Gardens – Four distinct monuments; the Manitoulin District Cenotaph, the Merchant Marines Memorial, the Youth in Partnership with Veterans Memorial and the Women’s Memorial stand in this tranquil memorial garden located on Hwy 551/542 between Mindemoya and Providence Bay/Spring Bay. These monuments serve to remind us of the contributions and sacrifices made for the causes of peace and freedom by the men and women of Manitoulin during the twentieth century. The Cenotaph’s flags are those of Canada’s Second World War allies.

Discovery Centre – Located at the foot of the boardwalk just off the downtown. Snack bar and change rooms, the building houses an interpretive centre, which has a fascinating mixture of biological, historical and fossil displays, as well as a snack bar, ice cream parlour and washrooms.

Boardwalk – Spanning the Mindemoya River and running for a considerable length of the beach, this wheelchair-accessible boardwalk is worth a stroll.

Town Square – A new and colourful downtown focus for this town.

Mindemoya

Pioneer Park – Access Pioneer Park off Hwy 551 through a covered footbridge and visit the reconstructed pioneer log home, barn and hiking trails.

St. Francis Of Assisi Anglican Church – Built in 1933 of local stone in the ancient Norman style of early European churches. The church contains a number of interesting and rare artifacts.

Little Current

Heritage Swing Bridge – Constructed in 1913 for rail traffic only, the bridge rested in the open position to allow for the frequent passage of coal freighters through the North Channel. Today the railway is gone, and the 980 tonne bridge provides a link for automobile traffic between Manitoulin and the mainland, excepting 15 minutes on the hour, when it now swings for the Channel’s plentiful cruise boat traffic. The unique swing bridge has been designated an Ontario Heritage Bridge.

Manitoulin Welcome Centre – The first building on your right after crossing the bridge onto Manitoulin, this aptly-situated building is home to the Island’s best selection of information on what to see and where to stay during your visit.

Low Island And Sisson Park – Within walking distance of downtown, Low Island is home to Little Current’s best beach as well as a walking trail, playground, picnic area, change rooms, softball, volleyball and soccer grounds, skateboard park, a splash pad, a pump track for bikers and vie de parcours-style workout equipment.

Farmers’ Market – Find the market downtown on Water St. first thing Saturday morning.

McLean’s Mountain Lookout – Located just outside Little Current, the lookout on McLean’s Mountain provides one of the most spectacular views of the North and Wabuno Channels with the LaCloche Mountains on the horizon. The lookout includes picnic tables, barbecues and washrooms.

Aundeck Omni Kaning

Four Directions Complex – State of the art community centre, gym and library in the heart of the village

Birch Island

St. Gabriel Lalemant Roman Catholic Church – This beautiful church was built in 1940 of area stone and cedar.

Dreamer’s Rock – Accessible only with permission, this is a place where youth would come and dream of their destiny following a fasting time.

Roosevelt Monument – The monument commemorating U.S. President F.D.Roosevelt’s wartime (1943) fishing trip to nearby McGregor Bay is at the main intersection of Birch Island.

M’Chigeeng

Ojibwe Cultural Foundation – A mixture of gallery (displaying the work of local artists who work in a variety of media), educational, resource and meeting space. The Foundation also includes a traditional healing lodge, elders room and gift shop.

Lillian’s Museum – A wonderful permanent collection of First Nation art and crafts, especially porcupine quill work, augmented by education videos on aspects of First Nation culture. It features a unique quill box museum.

Immaculate Conception Church – An architecturally interesting Roman Catholic Church which incorporates elements of native tradition in both design and content.

Kagawong

Bridal Veil Falls – The falls and river gorge are one of Manitoulin’s premier attractions. For the safest parking and most convenient access to both the falls and the trail system, park at the Kagawong Park Centre in lower Kagawong or near the river mouth in the vicinity of the Old Mill.

Vendors Market – A very busy market, every Wednesday 10 am to 3 pm during July and August, across from the Old Mill Heritage Centre.

The Billings Connections Trail – 32 heritage plaques and seven public sculptures located throughout the township, including on the river systems trails and in the hamlet of Kagawong. The plaques and sculptures are the result of a Canada 150mCelebration project. They provide information on township history and speak to the theme of municipal/community participation in Truth and Reconciliation.

Anglican Church – St. John the Evangelist Anglican Church, also known as the “Sailors” or “Boat” church is on the Kagawong waterfront, and features a pulpit fashioned from the bow of a pleasure craft wrecked off Maple Point with tragic loss of life.

Old Mill Heritage Centre – Located in the Old Mill (former pulp mill) building on the waterfront in Kagawong. The museum features local history and hosts special annual exhibits. The post office is an original structure, and features artifacts and information relating to early communication and transportation on Manitoulin Island. Featured in this building is also the home of Edwards Art Studios.

Beaches – The Kagawong beach is located in the heart of the village and is a wonderful kid-friendly sand beach. Another more expansive beach, Maple Ridge Sandy Beach, is approximately 2km around the bay from the village.

Old Church On The Hill – A gem of an entertainment centre located in a former church building that is the oldest structure in the municipality.

Gore Bay

Street Market – Every Friday, from 9 am to 1 pm daily. July and August, the main street becomes a busy pedestrian-only street market.

Gore Bay Boardwalk – An interesting stroll through and across the very bottom of Gore Bay. The interesting boardwalk leaves from Smith Park (an open field waterfront recreation area) adjacent to a basketball court/skateboard park. Walk the other way and you’ll find the tennis courts.

Noble Trail – Begins at Bay and Water streets intersection, climbs the scenic East Bluff to park lookout.

Gore Bay Museum – High above the downtown and adjacent to the courthouse complex. Unique exhibits and a busy gallery that anually features local artists. An extension of the museum is on the waterfront beside the boat harbour; the Harbour Gallery features artists, gallery space in a superb setting.

Harold Noble Memorial Park – Up on the East Bluff, this park and picnic area offers a panoramic view of the harbour and surrounding countryside.

Harbour Centre Gallery – At west end of waterfront. The Harbour Centre Gallery is occupied by many local artisans whose work if for sale in their shops. William Purvis Marine Museum upstairs.

Gordon/Barrie Island

Janet Head Lighthouse – Located at Janet Head at the end of Lighthouse Road, this Georgian-style lighthouse was built in 1879 and contains a fascinating history of maritime life, local development, and tragedy. Visit for a guided tour available a few afternoons each week in July and August.

Manitoulin Golf – On Golf Course Rd. off Highway 542. Nine scenic holes, club and cart rentals. Restaurant and bar.

Gore Bay-Manitoulin Airport – Following the Second World War, the Federal Department of Transport decided to establish an airport on Manitoulin to provide radio and weather information and an emergency landing centre. Since its completion in 1947, the airport has remained a vital asset for the area.

Beaches – Enjoy both of Gordon’s sandy beaches located at Tobacco Lake and Julia Bay. Use the children’s area at Tobacco Lake or practice your diving on the raft at Julia Bay. Visit the Salmon Bay Park on Goosecap Crescent on Barrie Island for a peaceful picnic spot overlooking Lake Huron. While you’re there, use the nearby boat launch to take a tour of the waters – the same can be done close to the Julia Bay beach.

Sheshegwaning

This proud community features Nimkee’s Trail and the Nishan Lodge.

Zhiibaahaasing First Nation

See the world’s largest Peace Pipe, Dream Catcher and Pow Wow Drum located in the center of the community in the park, all welcome.

Meldrum Bay

Net Shed Museum – Located in a building once used by fisherman to repair and store their nets, the museum is a tribute to the area’s marine heritage.

St. Andrew’s United Church and Community Hall – A well-kept church which has served the area for over 70 years is flanked by the nearby hall, site of numerous local events.