Whitefish Lake

Keen fishermen may find:

- Perch

- Splake

- Bass

- Walleye

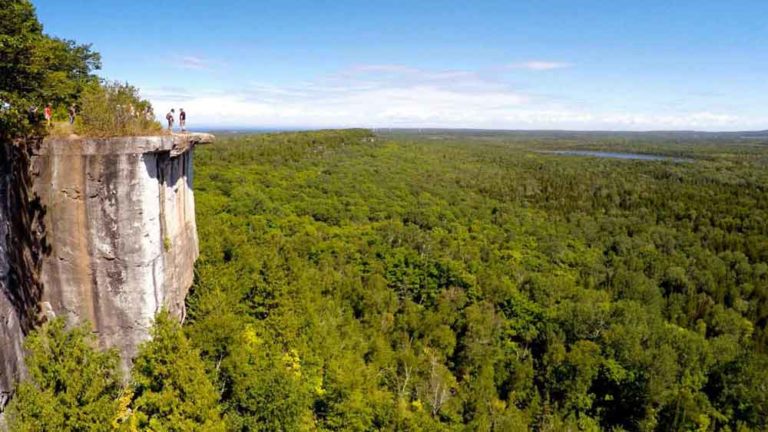

A deep triangular lake located midway between Lakes Manitou and Mindemoya, at the foot of the bluff that culminates in the Cup and Saucer Trails, you’d think that Otter Lake would be hard to miss. But it’s really more of a mystery.

You don’t see it from any major road, and even if you know where to begin looking for it, you still might not find the lake, because Otter Lake Road, at its juncture with Old Highway 551 presently lacks a sign.

To confuse things further, the lake is alternately referred to as Otter Lake and Whitefish Lake. Most residents of M’Chigeeng First Nation, which abuts the western half of the lake, call it Whitefish Lake, and it is marked this way on the Turners of Little Current map. But Otter,( or “n’gig,” in Ojibwe) is the preferred name now, at least officially, and M’Chigeeng historian Alan Corbiere believes this is probably the traditional name, too. “I have a map of Indian place names, and it refers to it as ‘n’gig.’”

Both names, however, are accurate, in that both otters and whitefish are populous here. One regular visitor to Otter Lake, who prefers not to be named, told me that he often sees otters along the lake’s northeast shore. “I’ll run with a trolling motor along there and you can hear them chewing on fish under the rocks. Sometimes they’ll dive in, and you can watch them come up with a little rock bass.

Whitefish are plentiful, too, although not in as large numbers, or hefty sizes, as they once were. According to the same angler, “they used to set nets in there, and would get whitefish as big as 12 or 13 pounds.” Gill netting doesn’t occur these days, but people still catch whitefish.

Cottages and a few year-round residents now ring the lake, which stretches about a mile and a half in length, but most are located in the southern, tapering portion, near the public dock. Here, the shoreline is clad in hardwood forest, and the water quite shallow. On the day I visited, in mid-June, a dozen kids from M’Chigeeng were horsing around on a swimming raft out front of a year-round home. They claimed the temperature was perfect for swimming, but I noticed a few goose pimples, and declined taking a plunge myself.

As you continue down the lake, heading north, the maple and oak forests begin to dwindle; white pines and poplars and cedars taking their place and dwellings begin to thin out too. The water, though, remains shallow for a good half mile or so, as well as remarkably clear. My unnamed angler estimated the visibility at 22 feet, adding that this clarity “makes it hard to catch fish, because they get spooked easily.”

As I paddled along I could easily make out the bottom of the lake, but no fish. Then I noticed a large pipe running along the lake floor and began to follow it to see where it would go.

The pipe doesn’t serve any purpose now (except perhaps as a haunt for smallmouth bass. A long time resident says he often sees them “hanging out there”). For many years, though, the Lakeview subdivision in M’Chigeeng drew its drinking water from Otter Lake. Now, all residents of the community get their piped water from West Bay, Well, almost all. Many of the lake’s residents still draw their water directly from their lake.

From my canoe, the pipe seemed like an endless, twisting snake. Except it probably wasn’t the pipe that was twisting, but just an effect of light filtered through the rippling water, and the yaw of my canoe. Sometimes I lost sight of the pipe in the shadow of the hull and then it would reappear on the other side of the canoe. And then, quite suddenly, it disappeared utterly from view. The lake had abruptly dropped off.

My guide says that, according to an MNRF map he saw once, the lake reaches depths of 170 feet. That’s pretty deep for a lake that’s not much more than a mile long, and not much more than half-mile widest. But it gets even deeper in one spot, according to my anonymous angler, he told me that he’s hit a place with his fish finder that registers 233 feet. “There must be a crevice down there,” he told me, “because 30 seconds later it comes back up to 60 feet.”

I didn’t bring a depth sounder, but the lake did begin to seem inkier and more fathomless as I paddled. It also seemed quieter and more beautiful. I saw only one other boat the day I was there, an aluminum boat with a small motor, whose occupant was quietly fishing. Personal watercraft are banned on Otter Lake, as is any boat motor over 9 horse power, so even in the busiest months of summer, I expect this lake is pretty peaceful.

Peaceful as it may seem, however, there are Ojibwe beliefs associated with the lake that suggest reason to be wary and respectful of its depths. In the book The Island of the Anishnaabeg, by Theresa Smith, both the late Mamie Migwams and Raymond Armstrong spoke about the presence of Mishebeshu, a lynx-like serpent with a long tail and horns.

When I spoke to Alan Corbiere about this, he acknowledged the traditional belief but was reluctant to name the spirit. “Some people, myself included I guess, don’t want to mention the name of the spirit, because he’s awake now, we don’t talk about these spirits in the summer, just the winter.

But he wasn’t averse to talking in general about the belief. “The idea, which doesn’t just occur here but on Lake Superior and across the whole region, is that these spirits live under the earth, and the way that they travel is through cracks, popping up in certain lakes.” Like Quanja Lake in Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, and Manitowaning Bay whose very name, properly Mnidoowaazhig, means “den of the spirit” or “subterranean cave of the spirit” in Ojibwe. Otter Lake is unusually deep, says Mr. Corbiere, with “a precipitous drop-off.”

And like Quanja Lake, it had been said to have and unusual colour, or “bad colour,” as some elders describe it in the Theresa Smith book.

As well, notes Mr. Corbiere, Otter Lake is a “high level lake,” considerably higher in altitude than either Lake Mindemoya or Lake Manitou. This, combined with its depth, fuels ideas of underwater passageways leading to the larger lakes.

Nearby places to stay, eat and play

Twin Peaks B&B

Cedar Grove Cottages

Pirate’s Cove Cottages

Island Spring Cottages

Island Sunrise Cottages

Cup and Saucer Trail

Big Lake

Lake Mindemoya

Maja’s

Wagg’s Wood

Mindemoya’s Pioneer Museum

Ojibwe Cultural Foundation

Lillian’s Museum

Golf

M’Chigeeng First Nation Traditional Powwow

Lillian’s Crafts

Neon Raven Art Gallery

Up Top Sports Shop

Stanley Park Campgrounds

My guide didn’t speak about Mishebeshu, but he did note that “old people used to say that if there weren’t fish in their net, they’d gone through the spring to Lake Manitou.” He admitted that the idea seems a bit strange, since Otter Lake is considerably higher than Manitou, but said that elders would speak of the “water being pushed up by pressure.” Both Mamie Migwans and Raymond Armstrong spoke of whirlpools that had spooked their parents or grandparents.

Whether by a sub-terrarium passage or not, Otter Lake is certainly spring fed. There are no streams flowing into it.

Another elder told me that you can feel the presence of the springs while swimming. “One moment you’ll be in cold water, and then it will be warm.”

The resident of Otter Lake wouldn’t rather be anywhere else. He loves the clear, deep water, alternately cool and warm, and still enjoys fishing here. A number of years ago he was instrumental in getting a stocking program going through the West Bay Fish and Game Club, in conjunction with the MNRF.

Walleye were stocked, as were splake. And although the Fish and Game Club is no longer active, and the splake never reproduced to the extent that was hoped, anglers does still catch splake and walleye, as well as perch, and of course, whitefish, which some believe are better tasting coming out of Otter/Whitefish Lake than Lake Huron, as “they’re not as oily here.”

As I paddled back down Otter Lake to the public dock. I knew nothing about possible underwater passageways to Lake Manitou or splake stocking, or the small beach where generations of M’Chigeeng residents had apparently arrived on foot, to camp. I just knew that I’d enjoyed my spin on this small, special, mysterious lake, and planned to come back.