Assiginack Museum

Manitowaning

A plaque at the entrance of the Assiginack Museum recounts the years of the ‘Manitowaning Experiment.’ After the Manitowaning Treaty of 1836 formally acknowledged Manitoulin Island as belonging exclusively to the Odawa, Ojibwe and Pottawatomi in perpetuity, the village of Manitowaning–Ojibwe for ‘den of the Great Spirit’–became the centre of the Canadian government’s Indian Department to ‘Europeanize’ the Native inhabitants, with an Anglican clergyman, a doctor and a teacher in residence.

The treaty of 1862, still controversial today, revoked the previous treaty, removed the Native population to assigned reserves–except for Wiikwemkoong that was, and remains, Unceded Territory–and opened the Island to settlement by Scots and Irish immigrants from southern Ontario. The ‘Experiment’ failed, and by 1867, the Indigenous residents had moved out and non-Native entrepreneurs moved in, building mills, homes, general stores, churches, hotels and setting up shop as blacksmith, cabinetmaker, tailor, bootmaker, doctor. By 1879, when The Manitoulin Expositor newspaper was founded and published there, Manitowaning was a most prosperous town.

The Assiginack Museum and Heritage Complex, opened as Manitoulin Island’s first museum in 1955, commemorates the origins of the town of Manitowaning and the Township of Assiginack on its grounds, in its limestone lockup and home for the jailer built on Arthur Street in 1878, and in the adjacent temperature-controlled exhibition and research facilities built in 2000 as a millennium project. This newer space is where curator Kelsey Maguire, who has a degree in English from the University of Guelph, a certificate in Museum Studies from the Ontario Museum Association and a special interest in genealogy, directs visitors who are looking for genealogical information on the area’s early families and their descendants, or for records of old properties.

The archives in the air-conditioned and heated facility are open to researchers by appointment year-round; catalogued are census print-outs, obituaries, family trees, files on existing headstones in cemeteries, records of family farms and properties. “The first Manitoulin Expositor is here,” says the curator, “and most all the hard copies of the paper. Although some are missing, the archive is mostly complete.”

In the exhibition hall below, a large collection of early iridescent lime green ‘vaseline glass’ glows in a glass case and rare china pieces that once graced the grand dining rooms of Manitowaning tastefully attest to the wealth of the townspeople in those days. Most of the museum’s extensive collection has been donated by local families whose ancestors settled here in the 1860s and later. “The biggest part of our collection is the china and glassware,” says Mr. Maguire, and there are enough display cases throughout the museum of the most fanciful blown glass and now-vanished porcelain patterns to amaze today’s visitors with perhaps more ‘minimalist’ domestic tendencies.

The spacious reception room features the affectingly executed scale model boats of Jacob C. Shigwadja; the late model-builder handcrafted large replicas of Manitoulin’s first ferries, including the Normac of the 1930s, the Norgoma and Norisle of the 60s (the latter ferry is berthed just down the street in Manitowaning Bay), and a five foot long cedar model of today’s Chi-Cheemaun, launched in 1974.

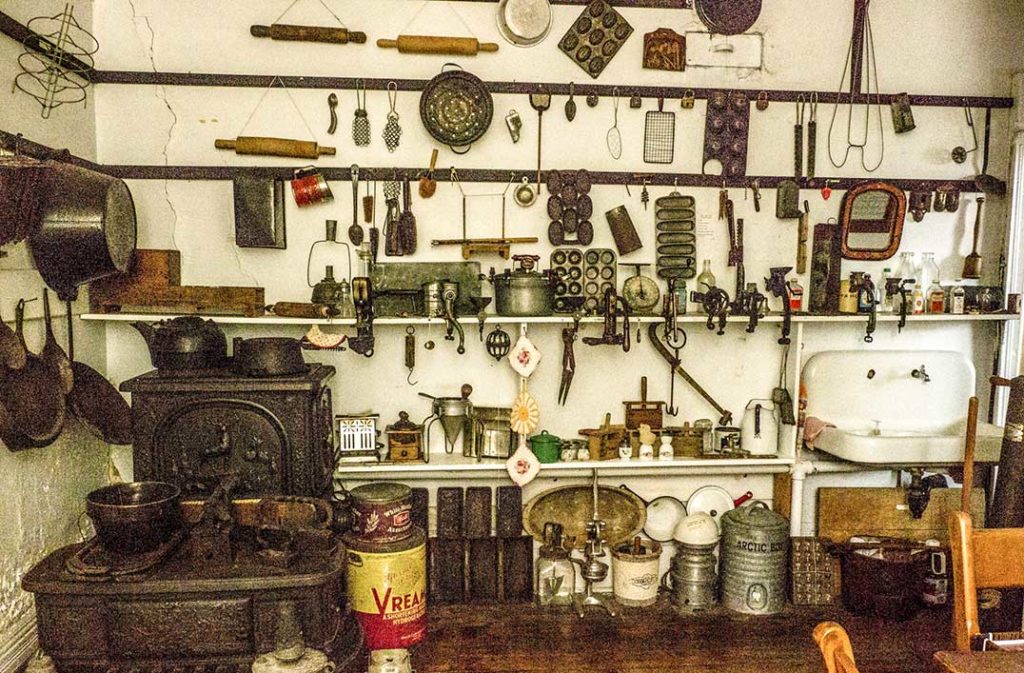

The original rooms house tools, taxidermy–no home of distinction was without at least a stuffed loon or fox somewhere–and early domestic implements, all witness to a long-gone way of life. A WWI and WWII military display shows rare vintage photographs of Manitoulin’s uniformed contributors to the war efforts; another room houses the last telephone switchboard in Manitowaning, in use until 1973 when dial phones took over, operated for a time by the Assiginack Museum’s former curator, Jeanette Allen.

We pause before a display of early children’s toys, including a gangly, crudely carved wood doll with hand-painted eyes and mouth: “This one,” says Kelsey Maguire, “was made by my great-grandfather, Jim Leeson, for my grandmother Amy Maguire, nee Leeson, circa the 1920s. It was loaned to the ROM’s Ethnology Gallery ‘Dolls’ Exhibit in 1979. It’s a ‘dancing’ doll. If you sit down and hold a wood shingle off your knee and bounce the doll up and down on it, the hinged legs make it look like it’s dancing.”

Among the picnic tables around the grounds are a restored one room log schoolhouse (1878), moved from Ten Mile Point, a driving shed and a blacksmith shop with authentic period settings in which to imagine life back then. One tiny log cabin, belonging to Philomene Lewis, was moved here from Wiikwemkoong. A photographic history of the area’s first schools is a paean to settler industry in establishing education early on. Here are Budge’s Settlement School (1874), Manitowaning’s Continuation School (1880), the Union School in the Slash (1883) and many more.

The curator, born a Haweater, has always lived in Manitowaning, and he is in his element here, amidst the local mementoes handed down through the generations: “This is my family,” he says, taking in the whole museum complex, from hardscrabble beginnings to later grandeur.

On Friday mornings in summer, a lively market and performance by Debajehmujjig theatre group fills the historic setting with local food, crafts and frolic.

The ‘Historic Walking Tour of Manitowaning’ map, available free at the front desk, lists over forty places of interest in the town.

Assiginack Museum and Heritage Complex: 125 Arthur Street, Manitowaning. Tel: 705-859-3905. Hours in July and August: Monday to Sunday, 10 am to 5 pm. www.assiginack.ca/assiginack-museum-heritage-complex

Article by