Sucker Lake

Keen fishermen may find:

- Perch

- Muskie

- Bass

With its unfortunate name and confusing status, many maps still mark a Sucker Lake Indian Reserve (No. 25), although it hasn’t been a reserve for years. Sucker Lake tends to discourage visitation.

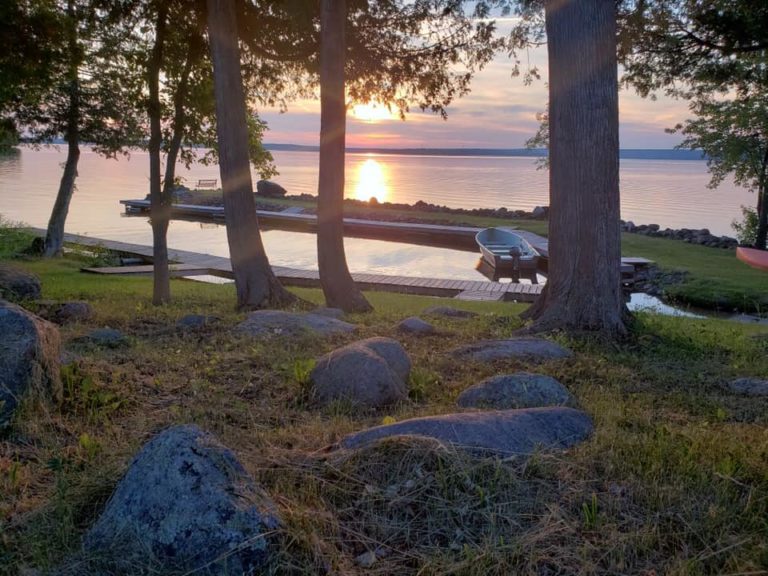

This is a shame, for Sucker Lake is an idyllic, peaceful spot with three uninhabited islands, a small public beach and boat launch, a fair number of perch and bass, and … absolutely no suckers.

“I’ve been coming back here for 50 years to fish and I’ve never seen a sucker in the lake,” says Murray Haner.

Mr. Haner grew up in Hilly Grove, near Manitowaning, and in 1969 acquired a farm and cottage property on the east shore of Sucker Lake. From May to November, the retired police officer doesn’t budge from his Sucker Lake retreat, while wife Gloria joins him as often as she can.

A neighbour of Mr. Haner’s also didn’t know why the name stuck to the lake but overserved “Your guess is as good as mine.” “One story I’ve heard is that it’s named after bloodsuckers.”

Bloodsuckers (ie. leeches) do, indeed, inhabit the lake, but not in any greater quantities than occur in many other lakes. The name still seems unfair.

A number of years ago there was a movement to have the lake renamed. Dave Ham, the reeve of Assiginack Township at the time (and now the municipality’s Mayor) recalls that “a chap from Little Current approached me, and said what an awful name for a pretty little lake.” An alternative name was shortly proposed, but there wasn’t enough support for it.

A long-time permanent resident of the lake, reflects, “it’s been Sucker Lake all these years, why change it now?”

Mr. Ham’s choice for a replacement name at this time was Assiginack Lake, a tribute to the famous and controversial native chief John Baptiste Assiginack (aka Blackbird) whose family resided on the Sucker Lake Reserve in the late 19th Century.

Although few people inhabited the reserve after 1968 (at its peak, there were about 50 people, according to historian Shelley Pearen), a few descendants of Assiginack stayed on through the early half of the 20th Century. Finally, around 1950, Eddie Clark, took over the reserve land from his uncle Angus Assiginack. From that time forward, the land, which spans 680 acres and touches on both Sucker Lake and Lake Manitou, was considered privately owned and no longer a reserve.

Ms. Pearen says that the reserve was never an ideal location, and that the First Nations folks who had previously lived at Manitowaning were given a raw deal in being moved there. A corrupt Indian agent named Dupont “wanted the good land for himself,” she says, “and bought up most of the town plot in Manitowaning in the names of relatives and friends.”

Being relatively remote, and not blessed with the numbers of fish found in the bigger waters, there was never much to sustain a community. “In this sense, Sucker Lake was aptly named, I suppose,” quips Ms. Pearen.

Could it be that the lake got its name because the Indigenous settlers there were “suckered” into living there? Probably not, but it’s an interesting way to look at it.

At any rate, people who seek out Sucker Lake today for an afternoon of fishing or a dip in in its relatively shallow waters (the deepest point is about 24 feet, with 12-14 feet being the usual), are not apt to feel hoodwinked or disappointed. If anything, they will likely be surprised by how scenic the lake is.

Not to mention quiet. With only a few residences on the entire lake, three of them seasonal, there’s plenty of uninterrupted shoreline and very little boat traffic.

Mr. Haner and wife Gloria occasionally take a canoe or pedal boat out on the lake. The latter is Mrs. Haner’s preferred mode of transport. “My grandson Ryan and I would go out in the pedal boat and fish for bass,” she says with a laugh. One bass which was caught again and again, and released each time, was dubbed “ol’ Scarface” by Ryan, now a Mindemoya businessman.

Timbering also used to occur at Sucker Lake. And evidence of the logging still shows up in the form of notched timbers, possibly used as boom logs, that lurk under the surface of the water.

Today, visitors can follow the Sucker Lake Road, found just north of Manitowaning, and very easily reach the public launch and beach on the lake’s northest shore.

While not a terribly big lake, the scenery is varied with steep bluffs on the west and southeast shores and the three islands strung out in a row in the middle.

And while the lake has a remote feel to it, it’s not really that far back in the bush. The Haners say they often hear the Chi-Cheemaun ferry blowing its horn at South Baymouth and Lake Manitou is just a mile or so to the east.

“Our son and Andre LeBlanc used to take a canoe and portage it from here over to Manitou,” says Mrs. Haner of those days gone by.

Presumably the portage is downhill, since Sucker Lake is quite a bit higher than Manitou. According to Dave Ham, who has flown over all of the lakes on Manitoulin at some point or other “Sucker Lake is 55 feet above Manitou, and 230 feet higher than Georgian Bay.”

That doesn’t make it the highest lake in the Island (Mr. Ham says Whitefish Lake, on the M’Chigeeng First Nation, has that distinction), but it’s up there, so to speak.

Sucker Lake does, on the other hand, probably have the distinction of being the least appealing by named lake on Manitoulin, although Mud and Mog lakes don’t sound much more tempting.

Nearby places to stay, eat and play

Wayside Motel

Camp Mary Anne Resort

Timberlane Rustic Cottages

L & J Trailer Park

Manitoulin Resort

Uncle Steve’s Park and Cabins

Bass Creek Resort

Red Lodge Resort

Lake Manitou

Windfall Lake

Garden’s Gate Restaurant

Bebamikawe Memorial Trail

Manitoulin Eco Park

McLean’s Park

Point Grondine Park

Assiginack Museum

Golf

Theatre

Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory Traditional Powwow

Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory Cultural Festival

Wass Tours

Mountain View Resort

Turtle Creek Lodges

Manitoulin Eco Park

Wee Point Resort and Cottages

That it hasn’t been renamed Assiginack Lake may have as much to do with uneasiness about the legacy of the famous and famously contradictory chief, as it does with tradition.

Mr. Ham notes that Chief Assiginack was unpopular among many First Nations people for signing the 1862 Manitoulin Treaty (which opened Manitoulin for settlement) and was effectively “booted out of Wiikwemkoong” as a result.

Assiginack was also known to shift allegiances at a whim between the Anglican and Catholic churches, says Mr. Ham, with the result that he effectively alienated himself from both at one time or another.

At the same time, though, Blackbird, was a very dynamic and intelligent man, a much-valued interpreter, and a great war hero, having fought many battles in the War of 1812 in defence of Canada against the United States invaders.

It is not clear how long he lived at Sucker lake, but Ms. Pearen says that “when he had to leave Manitowaning, that’s where he went.” In her book Exploring Manitoulin, she writes that the homestead of J.B. Assiginack exists near Sucker Lake, although nobody on the lake seems to know of its whereabouts.

Probably it has faded into the ground. The former reserve, however remains in the hands of the Clark family, who are descendants of the famous chief, so the thread has not been broken.