Stanley Park Campgrounds

Lake Mindemoya

Beautiful campsites for trailers and tents on Lake Mindemoya’s southwest shoreline. This central location is your ideal starting point for Manitoulin Island day trips and exploring. Stanley Park is also a great spot to just stay put and enjoy our fitness room, children’s play area, pavilion, sandy beach, fishing, marina, convenience store, canoe and paddleboat rentals and generally relax in our friendly environment.

Phone 705-377-4661,

info@stanleyparkcamp.com

StanleyParkCampgrounds.com

Also in the area

Stanley Park Campgrounds

Stanley Park Campgrounds Lake Mindemoya Beautiful campsites for trailers and tents on Lake Mindemoya’s southwest shoreline. This central location is

Up Top Sports Shop

Up Top Sports Shop About Up Top Sports Shop D.A. Williamson and Sons and the Up Top Sports Shop is

M’Chigeeng First Nation Traditional Powwow

M’Chigeeng First Nation Traditional Powwow September 2nd & 3rd The powwow at M’Chigeeng First Nation is held each year on

Golf

Manitoulin Golfing If you’re a golfer, by all means pack your clubs and come to Manitoulin Island. Manitoulin is a

Mindemoya’s Pioneer Museum

Pioneer Museum Mindemoya On Manitoulin, as each new township was surveyed after the still-controversial 1862 Treaty between the Anishinaabek and

Wagg’s Wood

Wagg’s Wood Difficulty ★★★★ • Approx. 1 Hour Car Park Public Toilets Pet Friendly Wheelchair Accessible About Wagg’s Wood Come

Maja’s

Maja’s Fresh Food • Home Baking • Events Wheelchair Accessible Wi-Fi Wheelchair Accessible Wi-Fi About Maja’s Maja’s is named for

Whitefish Lake

Whitefish Lake Keen fishermen may find: Perch Splake Bass Walleye About Whitefish Lake A deep triangular lake located midway between Lakes

Lake Mindemoya

Lake Mindemoya Keen fishermen may find: Perch Walleye Bass Whitefish About Lake Mindemoya On a satellite map of Manitoulin Island, Lake

Big Lake

Big Lake Keen fishermen may find: Perch Muskie Bass About Big Lake Less than two miles long and mile at its

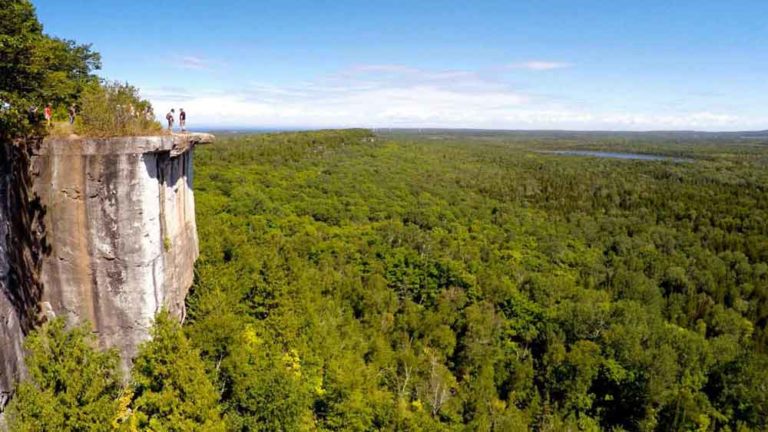

Cup and Saucer Trail

Cup and Saucer Trail Difficulty ★★★★ • Approx. 2 – 4 Hours Car Park Public Toilets Pet Friendly Wheelchair